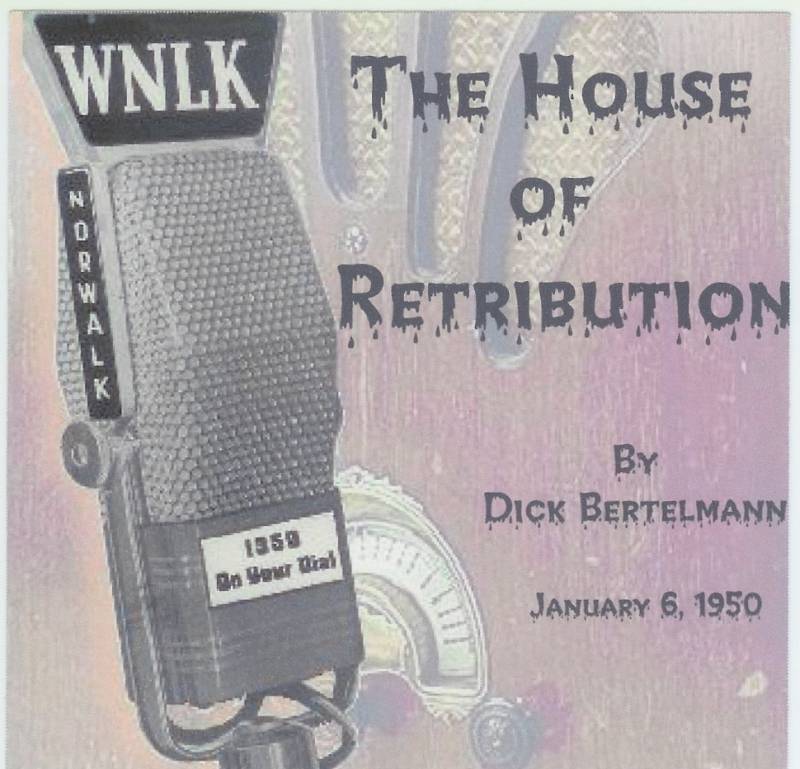

by Dick Bertelmann

Produced by the Community Radio Workshop on WNLK,

Norwalk, Connecticut - January 6, 1950

An original radio drama by

Dick Bertel before his days at WTIC

(Click on link above to listen)

| Program

notes by Dick

Bertel: WNLK, Norwalk Connecticut and the Magic of Radio Saturday, April 17, 1948 was a day I had been looking forward to for weeks. That was the day that Norwalk, Connecticut’s own radio station, WNLK, officially went on the air with 500 watts of power. I was a senior in high school in Darien, a town adjacent to Norwalk and was hoping to make broadcasting my career, so I was really excited. I had visited the station while it was still under construction in the hope of landing some sort of part-time job. Unfortunately, there was nothing available, but Milt Warren, the Program Director, who always called me “kid,” invited me back on opening day, an invitation I readily accepted. I peered through the glass windows that day and watched excitedly as one program after another was broadcast. I was even invited into Studio A, which was not on the air at the time, so that I could better see the disc jockeys at work in the control room. I was told that the engineers had actually tested the transmitter several times in the early morning hours a few days before the inaugural broadcast and had received confirmation of the signal as far away as Ohio. That impressed me very much. The station had three studios. Studio A was the largest and was designed for live programming. It housed a grand piano, 30 or so folding chairs for a studio audience and even a sound effects door on casters for use in dramatic programs. Studio B, designed for talk shows, was much smaller. Studio C was equipped with turntables as well as the control board. It was the central studio for newscasts and record shows and acted as the control room for the other studios. WNLK was not affiliated with any network and so originated all its own shows. The bulk of its programming consisted of records and included everything from pop hits to classical music. In those days program segments were still in vogue so that a station might feature a classical music show from, say, 10 to 11 AM followed by a noontime matinee of pop music and then salon music for an hour or so. The idea of a consistent format (rock, standards, country, etc.) was still years away. Although most of the music was played from commercial 78 RPM records, several of the shows would utilize transcriptions – 16 inch 33 1/3 RPM discs recorded especially for radio stations and usually of a higher quality, technically, than records. The transcription service would even provide scripts, using their discs. When WNLK first went on the air the station operated by law only from sunrise to sunset. This meant that the station signed on and off the air at a different time each month. This was economically very difficult because, during the fall months before Christmas when most stores were willing to spend advertising dollars, the station was on the air the fewest number of hours. In 1949 the station acquired a full time license, which solved that problem. However, after 7:30 or 8 o’clock in the evening the audience dwindled considerably, as listeners tuned into the network stations from New York or to New York television stations, which were already making strong inroads into the community served by WNLK. The station actually signed off the air at 10 PM each evening. Because they couldn’t sell their evening time, WNLK’s management was more than happy to turn some of it over to the community for local endeavors. This would serve them well when it came time to renew their license. A Darien resident named Bill Morton was given a half hour each Friday from 9:30 to 10 PM to produce dramas by the Community Radio Workshop, a group of local actors who also appeared in community stage productions as a hobby. Bill called the show “The Mystery Theater of the Air” and each week would produce an original radio drama with studio actors and sound effects. This is a recording of one of those productions and, as far as I know, is the only one that still exists. I wrote the play in a loose-leaf notebook while riding the New York New Haven and Hartford commuter train to New York University. It was patterned after network mystery shows that dominated the airwaves in those days. The cast assembled at the radio station at approximately 7:30 each Friday evening for the 9:30 broadcast. Typed copies of the script were handed out (carbon copies) and the actors would begin to read their parts, asking questions about the character, his or her motivations, etc. Bill Morton, the director, would suggest certain emphasis, inflections and interpretations. By about 8:30 or so the actors had marked their scripts appropriately and were ready for a dress rehearsal. One of the actors, usually one with a smaller role, would become the designated sound effects person. For this production actor Joseph Levicchi was chosen. Once the actors were tested for (voice) levels the dress rehearsal would begin. None of the actors wore earphones. Therefore, once the studio mic was turned on (which muted the studio speakers to avoid feedback) they were unable to hear any recorded sound effects or bridge music and had to rely solely on hand cues from the control room. Most of the time the actors took their cues from each other; however, on occasion they would have to pause for a sound effect before continuing. Because they couldn’t hear the effect they would wait for a nod from Bill to continue. Unless there was a disaster the dress rehearsal was not interrupted. When it was over Bill Morton would step out of the control room, make any last minute changes to the script and give final directions to his actors. When he returned to the control room to reassemble his sound effects records and transcriptions the rest of the cast would relax and get ready for the live show. They usually had ten minutes or so. All manual sound effects, such as the open and closing of doors and the striking of a match were performed by the designated sound effects person who worked with a separate mic mounted on a boom in an isolated corner of the studio. Most of the sound effects were on record and played from the control room. Director Bill Morton was in charge of this and personally operated the “board” or console. The sound effects records, all 78’s (ten inch discs that revolved at 78 revolutions per minute) would be lined up in a record rack in the order in which they were to be played. He had two turntables with which to work, on either side of the board. For the opening of “The House of Retribution” he had the running automobile disc on one turntable and the “skid” sound effect ready to play on the other. As soon as the skid sound was over, he would remove that disc, lay it flat on a table to his right and cue up the thunderclap sound effect. Now he was ready to bring the car to a stop. To accomplish this, he simply slowed the turntable down until it stopped. The coordination, which had to be perfect, was further complicated by the music bridges which were played from 16 inch diameter transcriptions. This required Bill, not only to change speeds from 78 RPM to 33 1/3 RPM (accomplished with a twist of a mechanical knob) but to cue up another pickup arm (each turntable was equipped with two) that would play the vertical cut on the transcription (as opposed to the lateral cut on the 78 discs). There was only one floor mic used for all the actors – an RCA 44-BX ribbon mic that was every announcer’s dream (because it tended to make your voice sound deeper). They would gather around it, usually two or three on each side, depending on how many were in the scene. As one actor moved his head in to deliver his lines the actor next to him would pull back to give him room. It was standard procedure for the day. If the script didn’t call for the actor’s services for a couple minutes or so he would step off to one side of the studio and simply follow along in his script. The program was recorded on my 1947 Meissner Model 9-1065 home disc recorder. This particular unit had a built-in AM radio, which enabled me to record directly off the air. Wire recorders were available commercially by this time and tape recorders were just being introduced in stores. By the time my play was produced on the “Mystery Theater” I had been hired as a weekend announcer at the station. My salary was 75 cents an hour. If the truth be known, however, I would have paid them for the opportunity they gave me. It is amazing to me that the actors, none of whom was professional, were able to accomplish so well all that was demanded of them. Notice their technique, how they interrupt each other when the script calls for it so that no one is left hanginh, and how effectively they use the mike to project their emotions. I believe many of them could have found jobs at the networks had they wished to pursue them. But that was not their aim. They were local people who lived and worked in the community or commuted to New York five days a week and who simply wanted an outlet for their talent on a Friday night. WNLK gave them that opportunity. The actors heard in this production were John

Tilley ----- Marty

Perhaps I’ve told you more than you wanted

to know. If so I

apologize.Harry Aiken ----- Cliff Madsen Eleanor Raddick ----- Jeannie Doug Bora ----- Gunther Shaw Joe Levicchi ----- Inspector Fulton Frederick Lamalfa ----- Sergeant Bill

Edwardsen is the announcer; he later went on to

becpme a major radio personality at WGY, Schenectady, NY.

Bill’s opening announcement to

the play was not recorded for some reason, so he graciously redid it

for

me many years later at my request.

Left to right: Unidentified, Unidentified, Joe Levicchi, Bill Morton, Dick Bertelmann, Harry Bertelmann, Doug Bora. Harry Aiken Now, enjoy the show. |